A Renowned Scientist Committed to His Faith

|

| Google Image |

A defining moment in U.S. history is occurring with little fanfare. Francis Collins, who has headed the National Institutes of Health for a dozen years, has announced that he is leaving that post by year’s end.

In a Twitter article, Nell

Greenfieldboyce and Scott Neuman describe the Institutes as “the largest funder

of basic and clinical biomedical research in the world.” Under Collins’

leadership, I would add, no institution has had a greater impact on American medicine

and Americans’ health.

Trained as a geneticist, Collins was previously

director

of the National Center for Human Genome Research, which was in charge of a

massive effort to fully identify humanity's genetic code. The project was

completed in 2003.

To give some

idea of the challenge, humans have between 20,000 and 25,000 genes. Each of us has two copies of

each gene, one inherited from each parent.

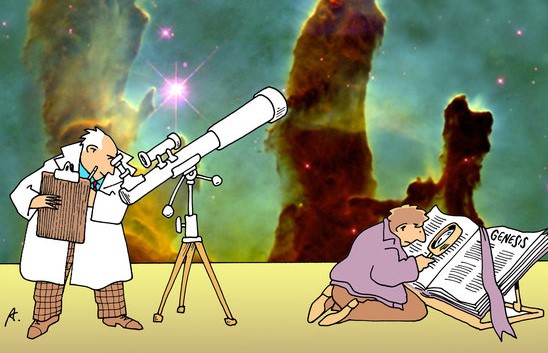

Willingness to Be Upfront

But in my estimation, Collins’ greatest

strength lies in his commitment to his faith and his willingness to be upfront

about it. I’ve written about him many times in this blog, using his famous 2006

book, The Language of God.

When working with the White House

staff for a speech on the completion of the DNA sequencing, Collins endorsed

the inclusion of the following paragraph in a presidential speech about the

genome project’s conclusion: “Today we are learning the language in which God

created life. We are gaining ever more awe for the complexity, the beauty, and

the wonder of God’s most divine and sacred gift.”

In his book, Collins writes that it

was “awe-inspiring to realize that we have caught a glimpse of our own

instruction book, previously known only to God.

|

| Francis Collins Google Image |

Faith was not part of Collins’

childhood. But when he was five years old, his parents sent him and a brother

to become members of a choir at an Episcopal church. They were told it would be

a great way to learn music but they weren’t to take the religious teaching

seriously. Collins followed their instructions.

At 14, he writes, “my eyes were

opened to the wonderfully exciting and powerful methods of science,” and science

became his career path. “By a few months into my college career, I became

convinced that while many religious faiths had inspired interesting traditions

of art and culture, they had no foundational truth.” He became an agnostic, then

an atheist.

Then things

started to change. In medical school, he writes, he was “astounded by the elegance

of the human DNA code, and the multiple consequences of those rare careless

moments of its copying mechanism.”

Very Powerful

When it came to

caring for patients in his third year, he began to notice “the spiritual aspect

that many of them were going through. …If faith were a psychological crutch,”

he concluded, “it must be a very powerful one.”

An elderly

patient, a woman of faith, asked him outright what he believed. “I felt my face

flush as I stammered out the words ‘I’m not really sure.’” He asked himself the

question, “Does a scientist draw conclusions without considering the data?

Could there be a more important question in all of human existence than ‘Is

there a God?’”

He determined

that all of his objections to faith were those of a schoolboy. That launched a

lifetime of re-discovery of Christianity and a faith from which he has never

looked back.

Comments

Post a Comment